In September I wrote a post about learning to write without spending any money. My point was that you don’t NEED creative writing courses, useful as they are: many of their elements are things you can access in other ways, more cheaply.

While many of the aspects of the creative writing course experience can be found online, I’m going to get old-fashioned for a moment and say that the one thing you can’t do without is books. You need the long, undisturbed periods of engagement that books provide to take on board some of the complex ideas about writing that some of these authors offer. Of course, if you’re writing you probably like books, so you probably won’t see this as a problem!

One of my biggest regrets about my writing journey is not discovering sooner what a tremendous depth of knowledge creative writing books offered. When I first had a publisher interested in my writing, years back, after a story I’d written was published in an anthology, I went off and bought the first ‘how to write’ book I could find. I’m not going to name it, because I hate criticising other writers’ work online, and anyway, this is going to make me look like an arsehole, but it all seemed terribly pointless and obvious. I knew books had to have beginnings, middles and ends. I knew characters had to be consistent and not change their eye-colour halfway through the book. I wrongly concluded that, firstly, this was typical of the level at which creative writing books were pitched, and secondly, that I knew it all. What I didn’t realise, of course, was that there was far more to it all than that: many ways less obvious than eye colour that a character could be inconsistent through the course of a book, and that while I knew a book had to have a beginning and an end I couldn’t actually have told you what that meant at anything more than a superficial level.

Once I finally got my head round how little I knew about the mechanics of fiction, a new addiction was born. I discovered that creative writing books aren’t just good for understanding how fiction works, they’re also there to help you solve problems: they help you understand why your hero is a bit lacklustre, or what kind of plot development would add intrigue to the boring bit. Now that I’m evangelical about it, of course, I’m always getting asked for recommendations, so here they are.

I currently have a shelf of about twenty or thirty that have been useful to me in some way, but as this is meant to be a ‘beginners’ post I’ll limit myself to talking about a few of the stars. These are all books that have worked for me – if anyone would like to add their own recommendations to my list, feel free!

To make the subject more manageable I’m going to divide them into categories, starting with:

1. Books for inspiration and ‘permission’ to write

Dorothea Brande – Becoming a Writer

This book is much loved for pointing out that if you write, that makes you a writer. I mostly like it for telling you that if you want to be a writer the first thing you need to do is to organise your life so that you actually have the time and space to write. People often miss the fact that they don’t have any time in their schedule, because they’ve been told that if they’re determined enough, they’ll do it. Well, so they will, but only if they remember the crucial intermediate stage of sorting things out so that they can.

Stephen King – On Writing

When you read this you end up wanting Stephen King to be your new best friend, which is not something you would expect from reading his books. It’s part honest memoir, part advice for new writers, and it talks you through his writing life (he accumulated more rejections as a teenager than many, less determined writers, do in a lifetime, and kept them all on a spike) and his thoughts on the essential ‘toolkit’ of the writer (tools being things like plot and characters, not highlighter pens and Tippex).

Anne Lamott – Bird by Bird

I haven’t read all of this but enough of my friends love it that it didn’t seem fair to leave it out. The title comes from her father’s advice to her brother aged ten, who was trying to write a big report on birds that he should have started months ago and didn’t know where to start – ‘Just take it bird by bird.’

2. Books on story and plot

Sometimes books primarily aimed at screenwriters turn out to be useful for fiction writers.

Robert McKee – Story

is one of those. This is the kind of book you should buy rather than get from the library, because you will want to come back to it.

John Truby – The Anatomy of Story

Truby is one of those writers who likes breaking down stories into their component parts and analysing them. You might not agree with his principles but many writers find them extremely useful as a way to build a story. I’ve found his insights invaluable.

3. Books to get you to aim higher

Jessica Page Morrell – Thanks, But This Isn’t For Us

This book bills itself as a ‘compassionate guide as to why your writing is being rejected’. It comes in particularly handy at revision time, but also helps you think about the eventual reader when planning the book. It’s also quite funny.

Donald Maas – Writing the Break-out Novel

It sounds a bit arrogant to be thinking about how to write your break-out novel when you’re still on your first, but this book is actually surprisingly good for the beginner. Maas uses his experience as a literary agent to analyse what ‘break-out’ books – where an established writer jumps into a whole new level of sales- have in common. The resulting discussion covers every aspect of the book from themes through characters to language.

4. Books on revising and editing

Renni Browne & Dave King – Self-Editing for Fiction Writers

This is an old favourite, much loved by writers and editors alike. It ranges from the basic (consistent point of view) to the subtle (eg the chapter on how to make your writing more sophisticated) but it is essential if you want to turn in a professional piece of work. It also has hugely difficult exercises.

David Madden – Revising Fiction

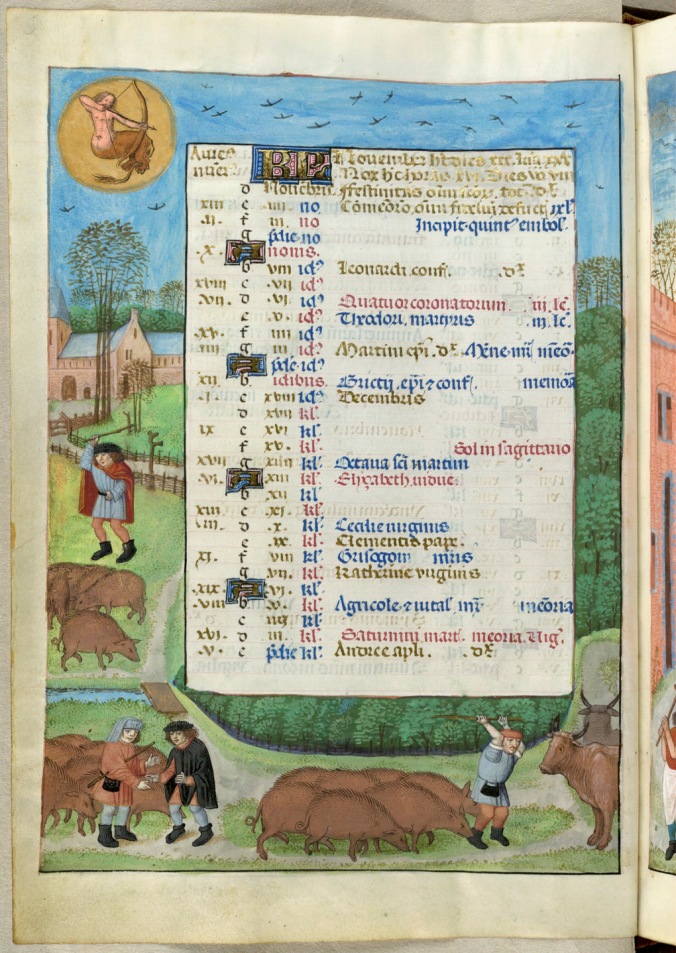

This book is hardcore. It’s like those medieval ‘have you ever fornicated with your sister? with a donkey?’ lists of sins you had to go through to examine your soul. For instance (opening the book at random): ’84. Are your transitions from one place or time, or from one point of view, to another ineffective?’ ‘184. [This is the killer:] Is your story uninteresting?’ There’s a particular moment when you need this book. It’s when you’ve revised four times already and your beta readers have run out of things to say but you’re just desperate to make your book better because you know it’s still not a millionth as good as Codename Verity and you would give your right arm or at least a little finger for any more clues as to what it might be. Just don’t even think about opening it until then.

5. Books on how to get published

Nicola Morgan – Write to be Published

The best thing about this is that it’s not just a book about the mechanics of getting published, it’s also a book about having the right attitude: getting published starts with writing something good. This is the one to recommend to anyone who goes around saying it’s not worth trying to be published because publishing’s a closed shop. Nicola Morgan brands herself as the ‘crabbit old bat’, which really just means she’s refreshingly blunt. She’s also done useful little e-books on how to write a synopsis and how to write a cover letter to an agent.

The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook (revised annually, published by Bloomsbury)

This used to be totally essential. These days, use it in conjunction with the internet – the listings of publishers and agents are pretty thorough but might not be completely up-to-date. It’s pricey for something you would need to replace every year but libraries are very good at stocking the latest edition.

And, for fun:

Sandra Newman and Howard Mittelmark – How Not To Write A Novel

The authors have had a blast making up lots of parodies of bad writing. Embarrassingly, I learnt a lot from it.