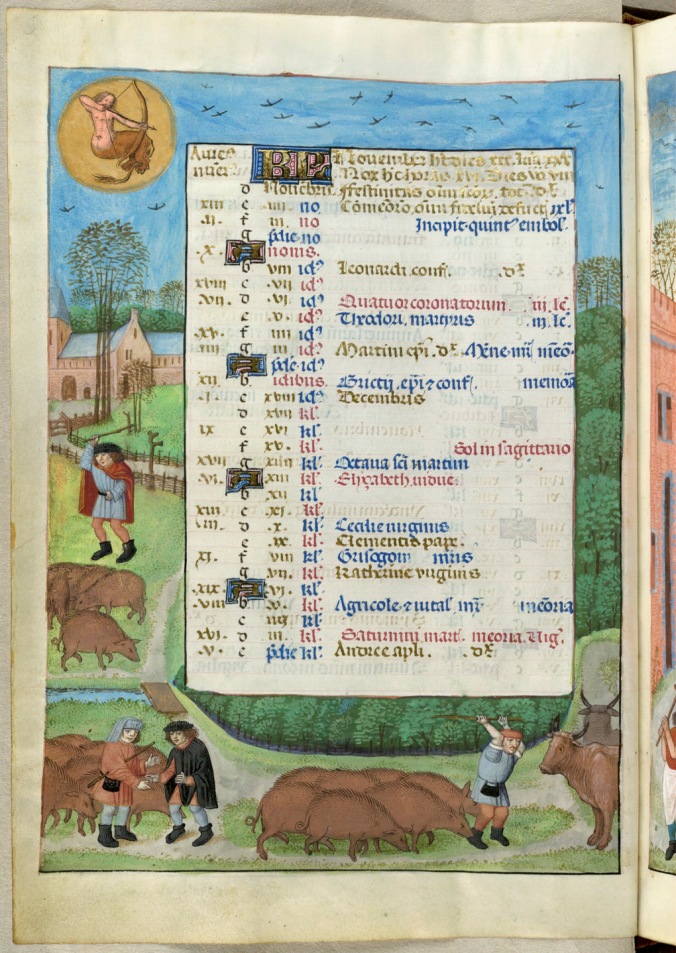

Calendar page for November with a miniature of a nobleman returning from a hunt, from the Golf Book (Book of Hours, Use of Rome), workshop of Simon Bening, Netherlands (Bruges), Additional MS 24098, f. 28v. Note the force-fed pigs.

I’m feeling a bit overwhelmed by the Novemberness of November today. It’s damp and drippy and everything in the garden is dying but the Christmas build-up hasn’t quite started yet, and… bleurgh.

I’ve decided this is the fault of twenty-first century life and if I was Tudor I would be far too busy for Novembery moping so I’m going to jolly myself along by thinking bit about what they would have been busy doing.

When I was writing Five Wounds, which is set mainly in the agricultural landscapes of the north, I was very conscious of how peopled the areas round settlements would have been. These days, farming takes very few people. One man can combine a field that would have taken a whole village to harvest in the past. We might notice the fields change colour from brown to green to golden, but it’s unlikely we’ll have much to do with it. In societies where more people are involved in agriculture, the changing seasons and hence the shifting calendar of agriculture have much more effect on what the people you know are involved in and what’s going on around you.

In a society without refrigeration, canning or air freight, of course, food will also be seasonal, and when the year is going to be shaped not just by the farming calendar but by the religious one, the annual round of festivals will give each month its particular character.

For this reason, one of my starting points for research was the Book of Hours. Books of Hours are devotional books, of which quite a number still exist from the fifteenth into the sixteenth centuries. They are often richly illustrated and, unlike wall paintings which rarely survive undamanged, they often survive as brightly and exquisitely detailed as the day they were painted. What makes them so useful for our purposes is that they generally include a calendar of church feasts, illustrated with full-page pictures representing the months of the year and the activities that were taking place each month. For the Tudors, 1st November, All Saints Day, was the first day of winter. But this didn’t mean farming activity stopped: work went on throughout the year.

Obviously, you have to be a bit careful if you’re writing about the north of England and you’re looking at a Book of Hours from southern Europe – the differing climates can mean different months for activities like harvests and planting. Another source, this time from England, is Thomas Tusser, who was born in Rivenhall in Essex. His ‘A Hundred Points of Good Husbandry’ was published in 1554. It gives rhyming advice for what to do in the garden and fields each month, for example,

‘Set garlic and peas, St Edmund to please.’

-a couplet which shows how the religious and agricultural calendars were intertwined in people’s minds even after the Reformation: St Edmund’s Day was celebrated today, the 20th November.Alongside cutting firewood, the most commonly illustrated activity in the Books of Hours November scenes is the fattening of pigs, by feeding them acorns. Acorns might not be anything other than waste now (unless you’re a squirrel) but in the Middle Ages, ‘pannage’, the right to feed your pigs in royal forests or on common land, was important. You will see people knocking down acorns with sticks, or hooking down the branches to reach them, and either driving your pigs into the forests to rootle under the trees or feeding them in troughs. In one picture the pigs’ heads are held in place over the trough by a yoke, to encourage them to eat as much as possible even when they were no longer hungry. Pigs were an important part of the rural economy; for some families, bacon would have been the only meat eaten on a regular basis. It was said later on that every part of the pig, ‘everything but the squeal’ was used.Some pigs would be fattened throughout November. Others would meet their end at Martinmas, the feast of St Martin on 11th November.This was the traditional date for slaughter of cattle. It was the time of year when animals were at their fattest but the grass was no longer growing fast enough to feed them. So they had to be slaughtered now, or fed on stored food through the winter, a burdensome expense. The slaughter was followed by feasting as people ate the meat that couldn’t be preserved. At this time of year, there was plenty of other food still available for a feast. In the garden, there would be cabbages and turnips, apples, pears and medlars. The woods would provide walnuts and chestnuts .While the poorer sections of society worked hard at salting and smoking meat from the Martinmas slaughter for the winter, the upper classes could hunt, with a range of game now in season, game birds and animals including hare and venison. The Golf Book of Hours shows a nobleman returning from the hunt. There are two horses in the picture but while he rides one, his servant has to walk, because the second horse is in use for carrying a deer, slung across its saddle.The importance of the job of slaughtering cattle – a job which would have required physical strength – was one reason why battles were so often fought after Martinmas. It’s far easier to drag yourself away from home once the work is done and you know your stores of food are laid in for the winter. One thing that intrigued me about the Pilgrimage of Grace was that the rebels were away from home through the month. I wonder if the women, left at home with the task looming, took the chance of waiting till their menfolk returned even if it meant slaughtering slightly thinner stock, or picked up the poleaxe and had a go themselves.

The British Library, Isabella Breviary. Additional 18851, f. 6v: calendar page for November. The pigs are on their way to market. I think something bad is going to happen to them, also to the cows on the right. I like the way the tall tree in front of the church just has a few leaves left. Mine looks like that too.

Of course, not everybody reared pigs just for subsistence. Some Books of Hours show pigs being driven to market in the town for sale. So if you lived in a town, November might have been the month when the streets were noisy with herds of squealing pigs being bought and sold. Then imagine how busy a street like the Shambles in York, where the butchers’ shops were, would have been, as all the bought-in beasts had to be slaughtered. These very noisome activities took place not in out-of-town abbatoirs as they do today, but in the very heart of towns, and butchers didn’t just deal with ready-killed carcasses, they were butchers because they butchered.

So, November. Lots of scoffing, but also plenty of gore. We will have get in some serious eating, anyway, before the abstinence of December and the Advent fast begin.

If you want a recipe, we’ll steer clear of the blood pudding and tripe, in favour of roasted crabs.

I used to think ‘when roasted crabs hiss in the pot’ in Shakespeare’s poem about winter meant the crustacea. Actually he was talking about crab apples – little, hard, tart apples that grow wild as well as in gardens.

And why roast them? Well, if you taste one they are mouth-dryingly tart. If you can be bothered to peel them you can use them just like a normal cooking apple, though with more sugar added. But for ordinary Tudors, sugar was in short supply. If you roast them, however, slowly, taking up to a couple of hours, you will find they have turned sweet enough to eat as they are. You can do it on a barbecue, or a baking tray in the oven, and add some cinnamon if you have some.

Happy November!